The Potala Palace was the political center of Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism since it was constructed under the direction of the 5th Dalai Lama in 1645. It is built on a hill, called “Red Hill” in the center of the Lhasa valley midway between the Sera and Drepung Monasteries, and near the old city and Jokhang Temple, the spiritual center of Lhasa.

It is an immense building with walls 5 meters thick at the base and 3 meters thick at the top. It is 16 stories high and has over 1,000 rooms, 10,000 shrines, and about 200,000 statues. This was the home of the current Dalai Lama until he fled to India during an uprising in 1959. The palace is now a museum with only about 20 monks present to keep it up. In the past as many as 300-400 monks lived in the palace.

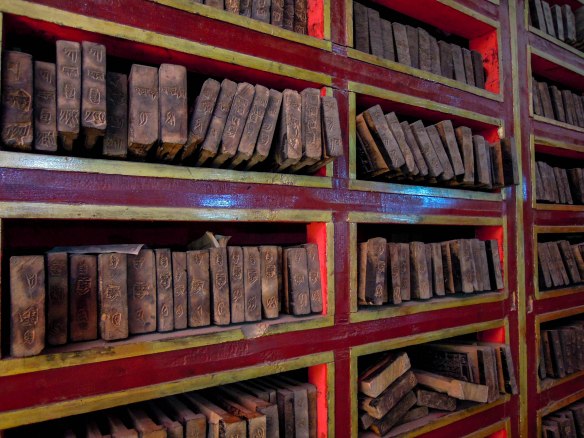

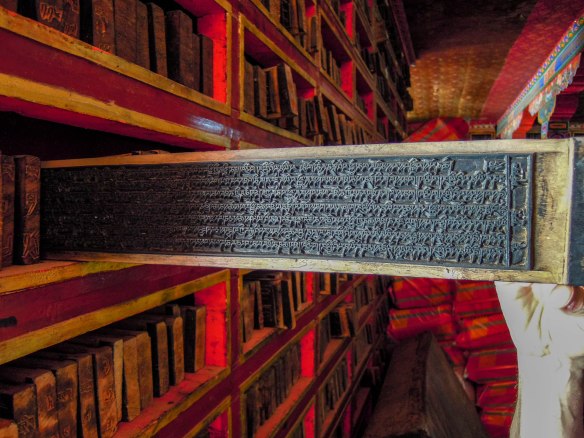

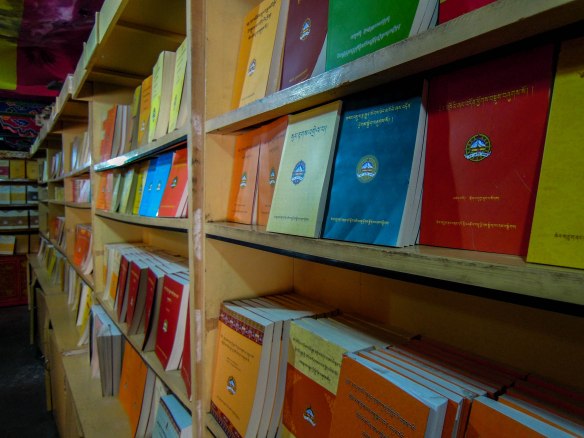

The palace is divided into two parts, the White Palace and the Red Palace. The White palace was devoted to secular things and was where the Dalai Lama had his quarters as well as offices, a seminary, and a printing house.

The Red Palace was devoted to all things spiritual and contains many different halls, chapels, libraries, and other places of worship. You can see the Red Palace in the center of the building above. I’m sure at one point in time the palace was on the outskirts of town, but now it sits right in the center of the city. There is a large boulevard that runs right in front of it and there is a large plaza-type park across the street. Most of the buildings all around in that area are Chinese and are not any different than any other Chinese city. Lhasa’s old town, the really interesting Tibetan part of the city, is about a 20-30 minute walk from the Potala Palace.

The number of visitors is restricted each day to prevent damage to the structure. I spent some time in Lhasa in May of 2012 and visited the Polala Palace. Visitors are only allowed in certain parts of the building. In fact, most of the halls are blocked to the public, including the former residence of the current Dalai Lama. The palace is a fascinating labyrinth of winding hallways, rooms, prayer halls, and so on. Tibetan pilgrims make up most of the visitors to the palace. They bring butter to add to the butter lamps as an offering; they also leave cash donations as well. Unfortunately, but understandably, photography was not allowed inside most areas of the palace. Of course, they wanted to sell you a very expensive book with photos of the interior.

One evening I strolled all the way around the hill where the palace stands. There are prayer wheels around most of the way and pilgrims regularly circumambulate the palace. At night the Palace is illuminated with bright lights. Behind the palace is a large park with a stage for performances. The evening I was there a Tibetan opera was being staged.

The whole time I was in the palace I had a strong desire to wander off and really explore the place. There were so many closed doors, blocked hallways, and entire buildings that we were not allowed to enter. I have read that it really is a spectacular building full of relics, art, scriptures, and so on. Who knows what mysteries lie behind those closed doors.