Group conciousness

What is it about Americans abroad. The seem to want to be heard, seen, acknowledged, liked, accommodated. The unflattering term “ugly American” refers to this perception that Americans are loud, arrogant, demeaning, and ethnocentric. Of course this is not true of all Americans, but unfortunately for some, it is true.

When traveling in China, I have found that it is better to do your best to blend in. Well, we can’t totally blend in because our physical features will always give us away. But there are several ways that you can better assimilate yourself into Chinese society. Remember China is a group oriented society, so blending in, and not standing out, is what the Chinese value.

Here are a few tips I have found to be valuable. These tips are not just valuable for Americans, but for any foreigner living or traveling in China.

• Avoid loud, flashy clothing.

Wear clothing that is similar to the clothes of those with whom you work or study. Err on the side of conservative dress. Women should avoid overly revealing clothing. Extreme clothing styles will only be a distraction and draw attention to you. This is especially true in professional settings. Shorts, sandals, a loud flowery shirt, and a baseball cap do not go over very well in China and will make you stand out like a sore thumb.

• Dress appropriately for the occasion.

If everyone at the office is wearing shirts and ties, or skirts and blouses, then you should also. Be aware that Chinese may dress up when you would not expect it, like for outdoor outings.

• Keep your voice down.

Americans can be very loud, even boisterous, especially in groups. When in public try to keep your voice down; avoid yelling, screaming, and loud laughter.

• Don’t assume everyone loves Americans.

You may feel like the world revolves around the United States and that everyone is enamored with American pop culture and lifestyle, but most Chinese are very proud of their heritage, ideals, and lifestyle. Be respectful of Chinese ways, even though they may be very different from what you are accustomed to.

• Avoid criticism and complaining.

You’re not going to win many friends if all you can do is complain about the pollution, the traffic, the humidity, the food, people spitting on the street, and so on. It is especially bad to compare everything to the United States and constantly mentioning how much better things are back home.

• Don’t insist on American style goods and services.

This is especially true in rural areas or smaller cities. Sometimes Western goods are not available or are at least hard to acquire. Potatoes are not common fare in most areas of China.

• Eat what is placed before you.

At least pretend that you appreciate the food and nibble on it. Shunning food given to you, especially at a banquet, can be very offensive to your hosts.

• Learn at least a few phrases in Chinese.

Learning a few phrases in Chinese and using them when you can will go a long way in China. The Chinese understand how hard their language is and appreciate when foreigners try to speak Chinese.

• Always remember that you are the guest.

The Chinese should not have to adapt their behavior to accommodate you. You should adapt your behavior to fit in with them.

• Make friends with the locals.

Sometimes Americans tend to hang out together in groups. Branch out and try to make friends with local Chinese. You will see and do things that most Americans will not have access to.

• Avoid common stereotypes.

Not all Chinese are good at math, are humble, and are martial arts experts.

• The Chinese are neither quaint nor cute.

With over a billion people, the Chinese can hardly be considered quaint. Some tourists make a big deal about the Chinese and Chinese things being “so cute.”

• Be inconspicuous with your camera.

Nothing screams tourist more than a large expensive camera around your neck, except maybe pushing into everyone’s faces and taking pictures. Keep your camera in an inconspicuous bag when not photographing. I will often leave my camera in my apartment or hotel, unless I am specifically going out to take pictures. Be respectful when taking photographs. It is best to chat with someone before asking to take their picture.

• Don’t always hang out at expat bars, hotels, and Western fast food restaurants.

Eat like the locals. Hang out with locals. Unfortunately many Americans spend a semester or two in Beijing or Shanghai, and spend the bulk of their time eating American food, and hanging out with other foreigners. That’s not why you are going to China.

• Smile.

Even if you are confused, frustrated, and don’t know what is going on, smile. It will ease the tension for both you and others.

• Take it easy.

Avoid public displays of anger or frustration. Keep your cool and be patient. Logic and reason do not always work. Trying to force your way seldom works. Try to understand the situation, be open to alternatives, and generally try to be pleasant no matter how ugly things get.

• Don’t flirt.

American style flirting is often misunderstood in China. While you may think it is all innocent and that not serious, Chinese usually interpret this behavior as serious affection.

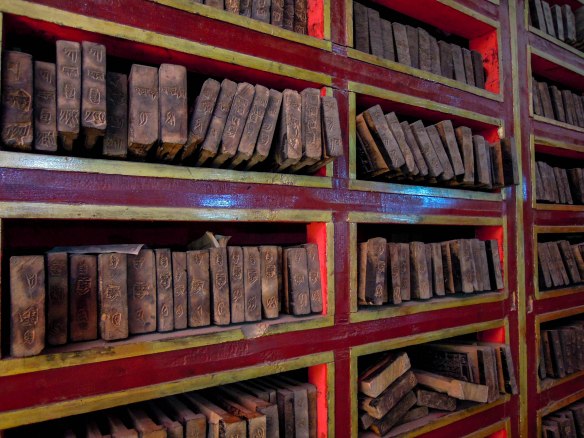

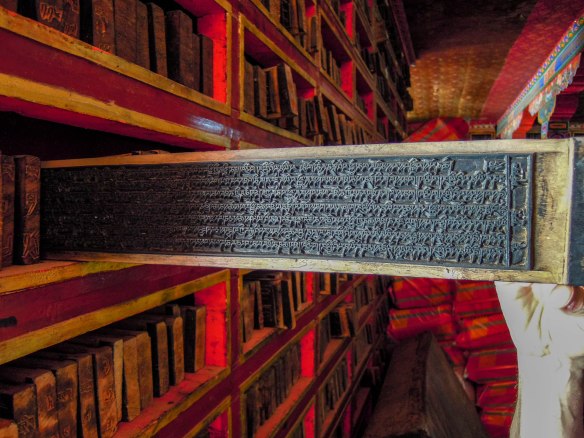

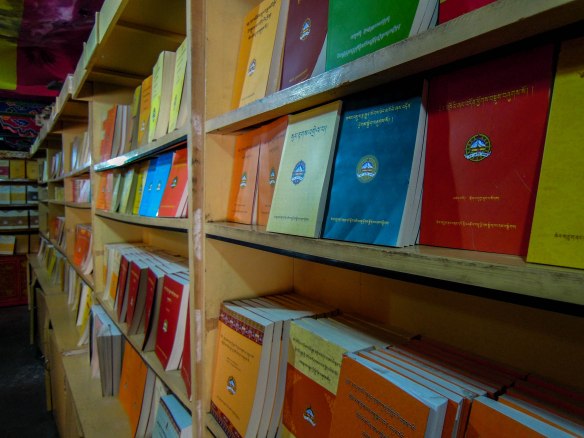

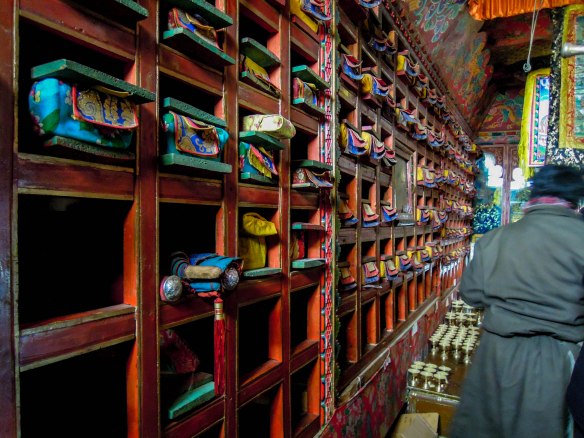

• Pay attention to mannerisms.

This is especially true with non-Chinese minority groups. They have different behaviors and mannerisms. If you are traveling to the Western provinces, such as Gansu, Xinjiang, Tibet, Yunan, and Western Sichuan, pay close attention to how people interact with each other.

• Be Humble.

Look people in the eye when you talk to them and acknowledge their humanity. Treat people with respect and dignity.

• Go slower, but go deeper.

Become a regular by frequenting the same places repeatedly. Get to know local people, like your neighbors, the lady that sells breakfast items from a cart on the street, the bicycle repairman on the street corner, and so on.

• Have patience with yourself and those around you.

China can be a difficult place. Allow yourself some time to and adjust and adapt to the differences.

• Embrace the culture.

Remember that you have a unique experience that may be over before you know it.

• Don’t expect things to be the same all over China.

Each area of China has different food, cultural icons, and ways of doing things. This makes your experience rich, exciting, and varied.

And lastly, be positive and have fun.